Dan Morrison reports for the San Francisco Chronicle:

Explosion of strikes rocks Egyptian firms

Thousands have walked off their jobs in a nation where such work stoppages are illegal — and many have won raises, benefits

Dan Morrison, Chronicle Foreign Service

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Kafr el-Dawar, Egypt — Ali Ghalab sat on a dusty office couch in a pinstriped suit, explaining why his 11,700 employees joined a wave of wildcat strikes that have shocked the government and paralyzed Egypt’s textile industry.

“It’s the Muslim Brotherhood,” the factory chairman yelled, referring to the officially banned Islamist movement, “and the communists. The Muslim Brotherhood stands behind every trouble in every single factory.”

A mile away, more than 1,000 strikers had barricaded themselves inside the textile plant in Kafr el-Dawar, a gritty town on the Nile Delta about 100 miles north of Cairo. They were demanding more money and greater opportunity for promotion. A shipment of cotton fabric destined for Turkey was locked inside with the disgruntled employees.

“Ali is a shoe,” they chanted. “He is useless.”

Rattled by rising prices, falling benefits and looming privatization, tens of thousands of Egyptian workers at state-owned industries have been in rebellion. In recent weeks, more than 35,000 workers at nearly a dozen textile, cement and poultry plants have gone on strike in a nation where any strike is illegal and even the smallest public protest can be squelched with police truncheons. Train engineers, miners and even riot police also have walked off the job or held demonstrations in the past 2 1/2 months.

“It’s very unusual. There’s been nothing like this in at least five years,” said Gamal Eid, a lawyer at the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights. “It’s not just the number of strikes, it’s the number of people involved.”

The strikers are bucking the government and their own unions to secure better wages and benefits at a time when inefficient state-owned companies are being sold off or scaled down. State-owned companies employ 10 percent of Egypt’s workforce of more than 22 million.

Late last month, Investment Minister Mahmoud Mohieldin set off a minor panic when he announced that 100 state-owned companies would be sold to private owners this year. New foreign investors and cash-strapped state corporations are trying to cut back on expenses at most factories, which are in heavy debt due to mismanagement and an excess of employees, labor experts say.

For more than a generation, Egyptian factories have existed primarily to provide employment, a policy the government of President Hosni Mubarak has been pulling away from since the 1980s. In 1993, the Kafr el-Dawar plant, for example, had 28,000 workers; today it has 11,700.

Labor Minister Aisha Abdel Hadi was not available for comment for this report. But in a recent interview with the Cairo daily, Al Masry al Youm, she said Mubarak “cannot sleep at night knowing there is one unhappy worker.”

The growing tension between management and labor broke into open defiance late last year.

In December, 18,000 textile workers at Mahalla, Egypt’s largest public-sector factory north of Cairo, took to the streets over low wages and purported corruption. They won an annual bonus worth 45 days’ pay — but may strike again to demand the removal of their local union leadership, who sided with management.

“It won’t be two or three days, it’ll be an open-ended strike,” said Karim el-Beheiri, 23, a Mahalla leader. El-Beheiri said managers were retaliating by evicting retirees from company housing. “It’s a witch-hunt against our parents,” he said.

In Egypt, there are 13 industrial unions whose top leaders are appointed by the state; local-level officers are elected with the support of state security agents. Local law also does not permit labor competition — a union can’t organize workers from another sector, and there has never been a legal strike in Egyptian history, labor experts say.

“Control over the unions has always been thought of as a national security issue,” said Ragui Assaad, an Egyptian labor expert. “It’s not about wages and collective bargaining, it’s about making sure the state has control over an active, organized, movement that can make trouble.”

Labor’s victory at Mahalla set off a wave of wildcat strikes, as workers from other factories began demanding similar bonuses. Employees at Kafr el-Dawar seized their plant early this month. Six days into the strike, company Chairman Ali Ghalab said the workers were deluded if they thought they could get the same bonus as Mahalla.

“We are probably the most in debt of all the textile companies,” he said. “If I had the money, I would pay them.”

He said workers benefit from frequent promotions, inexpensive housing and a company hospital that even offers free open-heart surgery.

“They are being manipulated,” he said. “The governor himself went to see them the other day. They were so rude.”

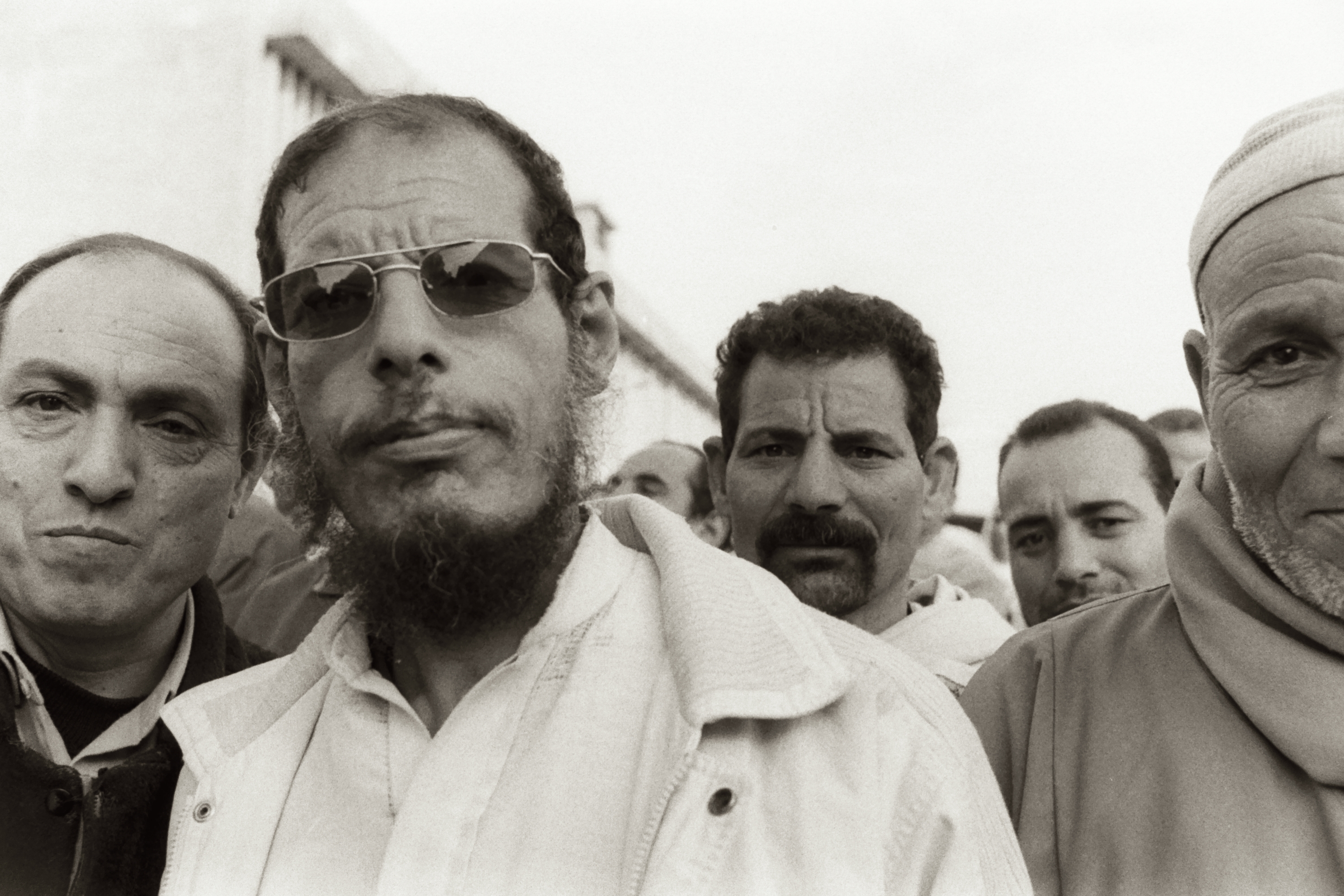

At the factory, a small crowd of police and intelligence men listened to growing chants inside. A few striking workers laughed at management’s claims of health care and the opportunity of promotion. One said a friend had contracted hepatitis C after having a molar pulled by a company dentist.

The workers denied that the Muslim Brotherhood — whose members run as independents and comprise the largest opposition block in parliament — is linked to their strike.

“When the ruling party has a bad dream, they wake up and blame the Muslim Brothers,” said Khalid Ali, a 36-year plant veteran. “You know why we’re striking? Conditions have reached a dismal level. It’s bad for workers all over Egypt.”

Egypt’s growing economy can’t keep pace with the more than 600,000 graduates from technical colleges who enter the workforce annually. State-subsidized fuel prices rose 30 percent last year, and inflation passed 12 percent, while salaries have remained stagnant or fallen slightly, according to the Economist news magazine.

Egypt’s teachers routinely charge for after-school tutoring in exchange for passing grades, parents say.

“If you earn 500 pounds (about $87 a month), you have to pay 400 just to tutor your kid,” said Khalid Ali, citing a typical factory salary. Other men showed scars, a missing finger, a crooked shin and a gashed forearm — all the result of factory injuries.

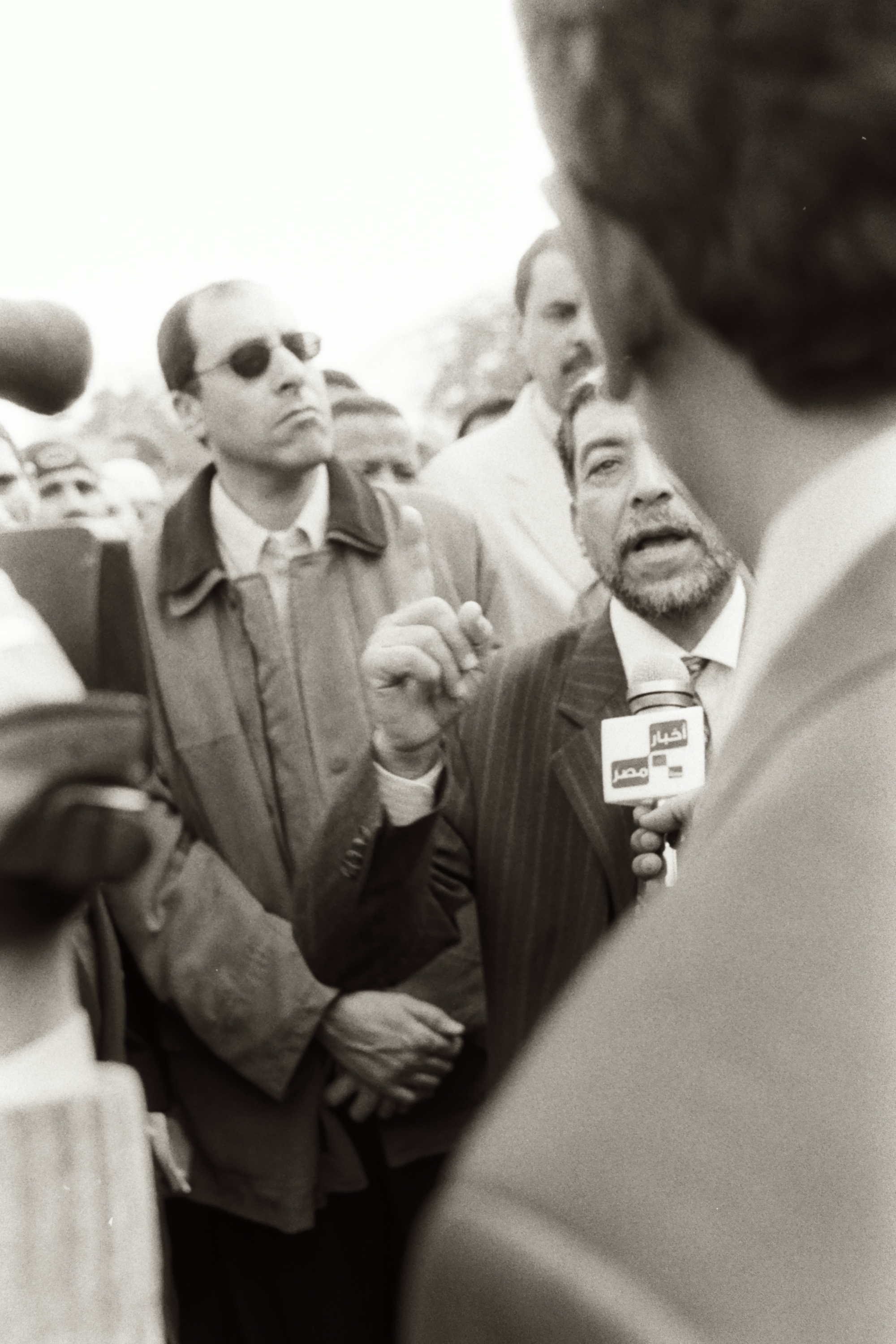

As word that a compromise had been reached between Kafr el-Dawar workers and the Labor Ministry, cell phones rang, strikers chanted and held up their fingers in the V-for-victory sign. The government agreed to give them a cost-of-living allowance equivalent to a 45-day bonus, increased promotions and improved health care facilities among other guarantees.

As workers streamed into the factory’s concrete yard, a convoy of cars arrived carrying the local governor, Muhammad Shaarawy. A former general in the state security directorate, Shaarawy announced the deal via a weak bullhorn.

While Egypt’s security agencies typically crack down on protesters seeking political reform, they are often more tactful in their approach to labor uprisings, which can involve tens of thousands. In fact, security agents sometimes act as mediators during wildcat strikes, says Gamal Eid, the human rights lawyer.

They will do “whatever it takes to keep the pressure down,” he said.