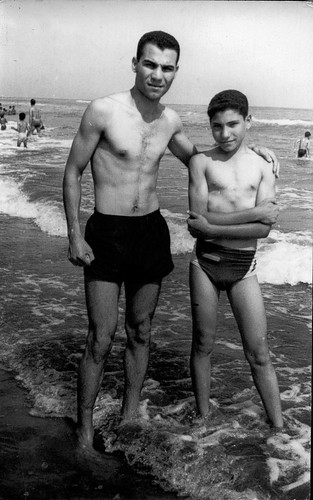

Another pic from the Family Album: My dad, standing to the left, with his youngest brother Mostafa, in Port Said, August 1965. Mostafa was to take photography professionally from the beginning of the 1980s, and opened with the help of my dad “Studio el-Hamalawy” in Tanta. Mostafa passed away in 2006.

Category: Photos

Rashad

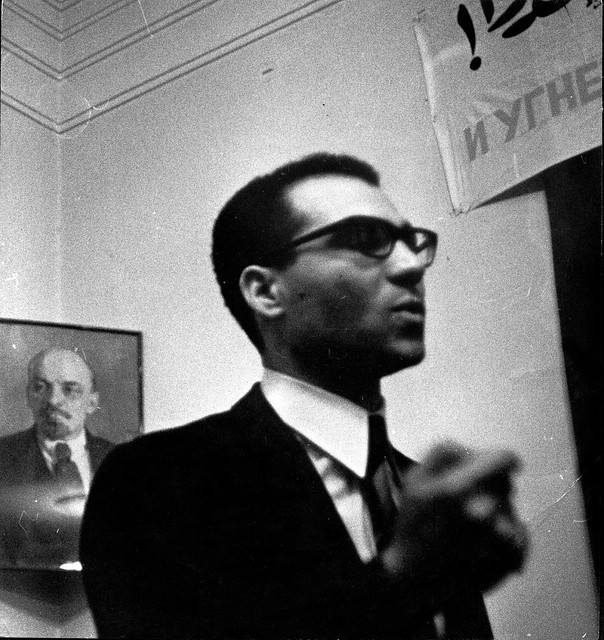

Another pic from the Family Album:

My dad, standing first to the right, wrote on the back of the photo, “Fayoum” but no date is mentioned. I’d suggest it was taken sometime in 1966 or 1967 before the June War. One of the persons I recognize in that pic is his best friend, whom I won’t name or point out at the moment since he’s still alive and I didn’t consult with him whether he wanted to talk about this part of his and my dad’s lives or not. But it was through this friend that my father was first introduced to Fatah, during his post-graduate years.

Launching the “Palestinian Revolution” in January 1965, Fatah earned the suspicion and the denunciation of the Nasserist regime. Despite using the Palestinian cause as a cornerstone for his legitimacy in Egypt and the Arab World, Nasser was sure to exert full control on the Palestinian armed activities, setting up the PLO and imposing his stooge Ahmad el-Shoqueri whose job was praising Nasser and making sure no “miscalculated and adventurist” armed Palestinian resistance operations occurred against the Zionist state.

When Arafat and his posse took up arms in 1965, Nasser naturally viewed them with suspicion as “Syrian agents” and accused them of “adventurism.” News about the group’s (few, but were picking up) armed operations were censored in the Egyptian state-controlled press. But news were leaking into the Egyptian universities about this new mysterious Fatah group through the Palestinian students…

My father’s best friend was dating, and later married, a Palestinian who was affiliated to Fatah, and was studying in Cairo when they met and fell in love. Both him and my dad were staunch believers in Nasser, and sincerely believed he was working towards liberating Palestine. But the two were also on the more radical left side of their peers in the (regime-sponsored) Organization of the Socialist Youth. They looked up to Nasser, but felt “more was needed.” So they got into an endless cycle of love-hate towards Nasser, and already felt before the 1967 defeat that some “extra push” was needed to make Nasser tackle this or that.

The 1967 defeat came as an earthquake and shattered many of their illusions, radicalizing them further to the left. While his friend went on to get more involved in supporting Fatah, my father started sniffing around for a communist organization to join.

Rashad

Here are two more photos from the family album:

Standing third from the right with his hands in his pockets, my father, Muhammad Rashad el-Hamalawy (1942-2000), wrote on the back of the photograph in Arabic “Madrasset el-Aqbat el-Thanawiya bi-Tanta (The Copts Secondary School in Tanta), 1959.”

This was my father’s final year of high school. He must have been 17 or 18 in this pic. That year was a turning point in his life, as he ranked the third on the republic in the Thanawiya Amma exam, and “was honored” to be among the students to shake Nasser’s hands on Eid el-‘Ilm (Science Day). My father fell in love with Nasser on that day… To be more accurate, his love for Nasser grew exponentially on that day but had already started three years earlier with the 1956 Suez war. He used to recall with humor how his attempt to lie about his age to join the “Popular Resistance Brigades” was exposed easily coz he was short. My father was 14 when the war broke out, and had already spent sometime with the Muslim Brotherhood Boyscout group, followed by few months in a communist cell in Tanta that operated out of some bookshop in the town. I cannot remember however which organization it was. All I remember is that he said his experience did not last more than few months, as the bookshop was closed down by Nasser’s “revolutionary” regime and the organizers were taken away to the gulag and were not seen for years…

But 1956 and Nasser’s defiant stand in the face of the three invading armies (though of course the military performance was a disaster but this was easily forgotten) was to inflame the emotions of my young dad and millions of other Egyptians and Arabs across the region. Nasser became his personal hero. Coming from a working class family employed by the railways who moved between the Gharbeia and Sharqiya Nile Delta provinces, he felt direct social gains from the new republican regime. He was the first to attend university in his family, and became “ostaz game3i” (a university professor), a job which together with engineering and medicine (or a career in the army of course) was basically the ACE dream for all aspiring Egyptian families in the 1950s and 1960s.

But the 1967 defeat was to hit him hard, together with millions of his fellow citizens, whose faith in Nasser was unquestioned till June of that year, regarding him as the sole agent of social change and liberation in the face of imperialism and Zionism.

It’s very fashionable in ME politics literature to cite the 1967 defeat as the birth pang for Islamist politics depicting its rise as a mechanical reaction to the failure of secular nationalism. This is wrong… The 1967 defeat caused a radicalization further to the left among a considerable section of the Egyptian youth, whose dreams for socialism, equality and liberation were betrayed by Nasser as they saw it. My father went back home–after a meeting at the Arab Socialist Union on the night of the 8th of June, where he and other high ranking members of the Organization of Socialist Youth (the regime’s youth group) were told the news of the defeat to be announced to the public on the following day–tore down Nasser’s poster he had on the wall of his room. It was replaced few days later with Mao’s, followed with a resignation from the membership of the Arab Socialist Union. Nasser’s propaganda books in his library were replaced with Lenin’s “What’s to be Done?” and whatever communist literature he could put his hands on at the time.

Even before the internet radical ideologies moved by osmosis. Egypt was hardly isolated from the radical currents that were sweeping the globe by the late 1960s… Guevara, Mao, Sartre, the universities rebellion, the Vietnam war.. all names became familiar to the rebellious students in Western Europe the US with the 1968 events.. but they were also familiar to their Egyptian and Arab counterparts. With the revival of the labor and student movements in Egypt in February 1968, the “Third Communist Wave” was born, which will attempt to build presence in the industrial towns and universities campuses, and were to lead the student opposition to the Sadat’s regime, and engage in the escalating social struggle that was to explode into the 1977 Intifada.

My father took off in 1968 to Moscow, where he lived for five years, doing his PhD at the Plekhanov Institute. He used to joke about how he got disillusioned with the Soviet Union “one week” after his arrival. He was standing in the Red Square queuing to visit Lenin’s mausoleum, when suddenly he saw a soldier with a stick shouting at the crowd something like: “Stand in line you animals.” My father was shocked. How come someone from the “Workers’ Militia” describe his fellow citizen workers as “animals?!” he wondered. Of course this slur was just the beginning… Over the course of five years, my father would be receiving one shock after the other, that contradicted everything he thought what the “workers’ state” should be like…

Yet he still labeled himself as a “communist,” and embraced a mishmash/cocktail of ideas that included elements from Stalinism, Nasserism, Dependecy Theory, Existentialism.. Too bad he didn’t come across Cliff’s ideas. His attempt to form an underground organization among the radical leftist Egyptian students in Moscow (and there were plenty of them back in the day) did not progress well. But that’s another story.